This blog series expands upon a presentation given at DEF CON 29 on August 7, 2021.

Phishing attacks are starting to evolve from the old-school faking of login pages that harvest passwords to attacks that abuse widely-used identity systems such as Microsoft Azure Active Directory or Google Identity, both of which utilize the OAuth authorization protocol for granting permissions to third-party applications using your Microsoft or Google identity.

In the past few years, we have seen illicit grant attacks that use malicious OAuth applications created by attackers to trick a victim into granting the attacker wider permissions to the victim’s data or resources:

- Phishing Attack Hijacks Office 365 Accounts Using OAuth Apps, Lawrence Abrams, 12/10/2019.

- DEMONSTRATION – ILLICIT CONSENT GRANT ATTACK IN AZURE AD / OFFICE 365, Joosua Santasalo, 10/25/2018

Instead of creating fake logins/websites, illicit grant attacks use the actual OAuth authentication/authorization flows in order to obtain the OAuth session tokens. This has the advantage of bypassing MFA authentication, with permanent or nearly indefinite access since the OAuth tokens can be continually refreshed in most cases.

In this blog series, we will review how various quirks in the implementation of different OAuth authorization flows can make it easier for attackers to phish victims due to:

- Attackers not needing to create infrastructure (e.g., no fake domains, websites, or applications), leading to easier and more hidden attacks

- An ability to easily reuse client ids of existing applications, obfuscating attacker actions in audit logs

- The use of default permissions (scopes), granting broad privileges to the attacker

- A lack of approval (consent) dialogs shown to the user

- An ability to obtain new access tokens with broader privileges and access, opening up lateral movement among services/APIs

Finally, we will discuss what users can do today to protect themselves from these potential new attacks.

In Part 1 of this blog series, we will provide an overview of OAuth 2.0 and two of its authorization flows, the authorization code grant and the device authorization grant.

OAuth as we know it

The OAuth 2.0 RFC 6749 was released in October 2012, and OAuth has become the standard for authorizing Internet interactions based on your Microsoft Active Directory, Google Identity, or with vendors such as Paypal or Login With Amazon.

With OAuth authorization flows, users benefit from:

- Not sharing their username and password with 3rd-party websites or applications—authentication is handled by the identity provider alone

- Using a centralized set of identity credentials across applications, simplifying password management

There are multiple authorization flows within the OAuth 2.0 specification that handle a variety of authorization cases. The flows include web applications/sites, mobile/desktop applications, and devices such as Smart TVs (e.g., authorizing streaming video content to your TV). At a high level, all of the OAuth authorization flows involve the following steps in some way:

- An application directs the user to the identity/authorization provider for authentication and authorization of access to the user’s data or resources.

- The user successfully and securely authenticates with the identity/authorization provider

- Depending upon the flow, the user may be presented with a consent screen that clarifies which permissions are being requested

- After successful authentication and authorization, an OAuth access session token is created that allows API calls using the user’s identity with the permissions approved by the user

- The application obtains the OAuth access token using an authorization code

- The application then accesses the data or resources required. OAuth access tokens usually expire in one hour, but refresh tokens are usually also returned to the application, which can be used to create new access tokens, usually indefinitely by default.

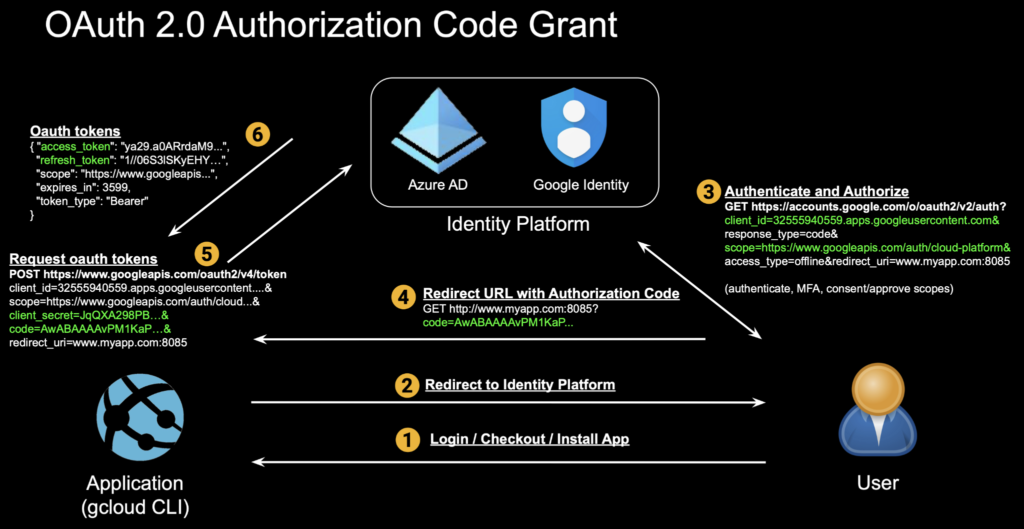

Most of us have encountered OAuth as users when authorizing access by applications such as Google Drive, Gmail, Outlook, or OneDrive. This is the most common flow, called the OAuth authorization code grant. Here we authenticate and authorize the Google Cloud CLI, gcloud, to access our GCP environment:

1. Application requests authorization by redirecting the user to the identity/authorization provide

$ gcloud auth login [email protected] --force

Your browser has been opened to visit:

https://accounts.google.com/o/oauth2/auth?response_type=code&client_id=32555940559.apps.googleusercontent.com&redirect_uri=http%3A%2F%2Flocalhost%3A8085%2F&scope=openid+https%3A%2F%2Fwww.googleapis.com%2Fauth%2Fuserinfo.email+ht...

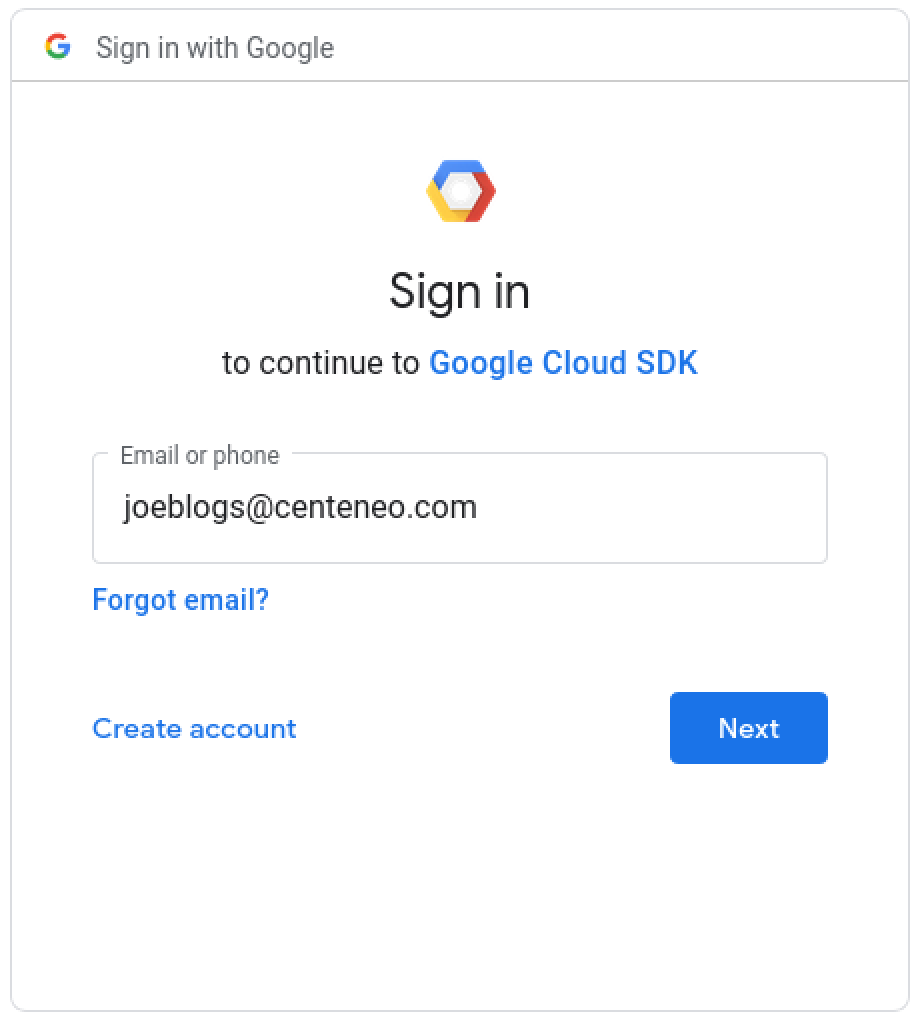

2. User authentication: Enters username

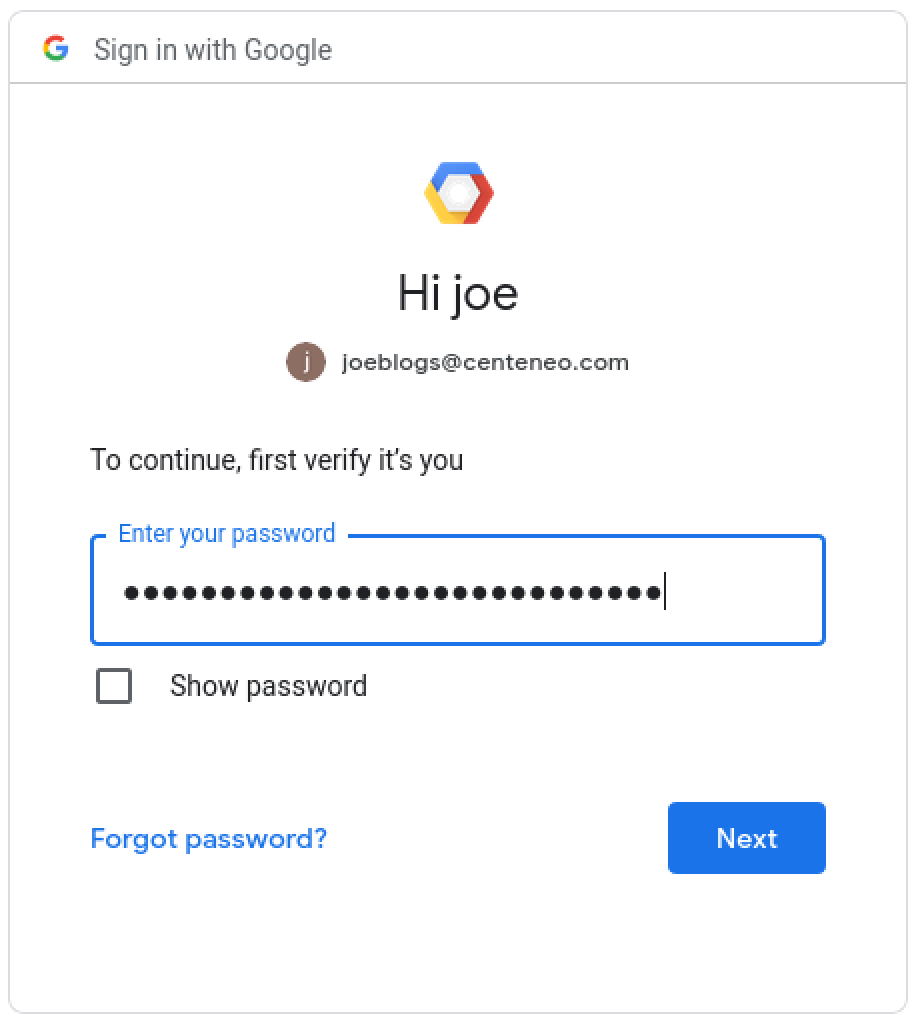

3. User authentication: Enters password

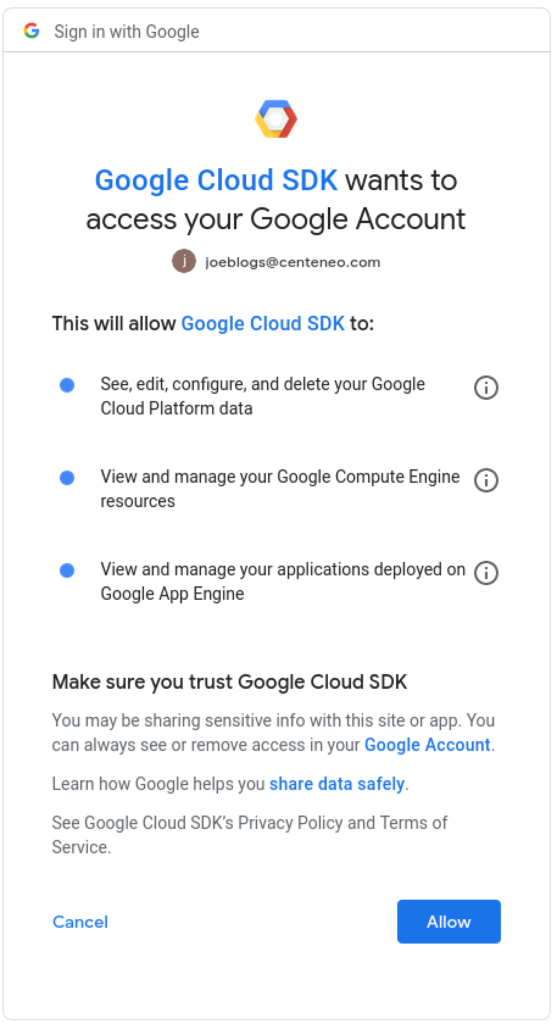

4. User authorization: The user is presented with a consent screen and approves the scopes requested by the application

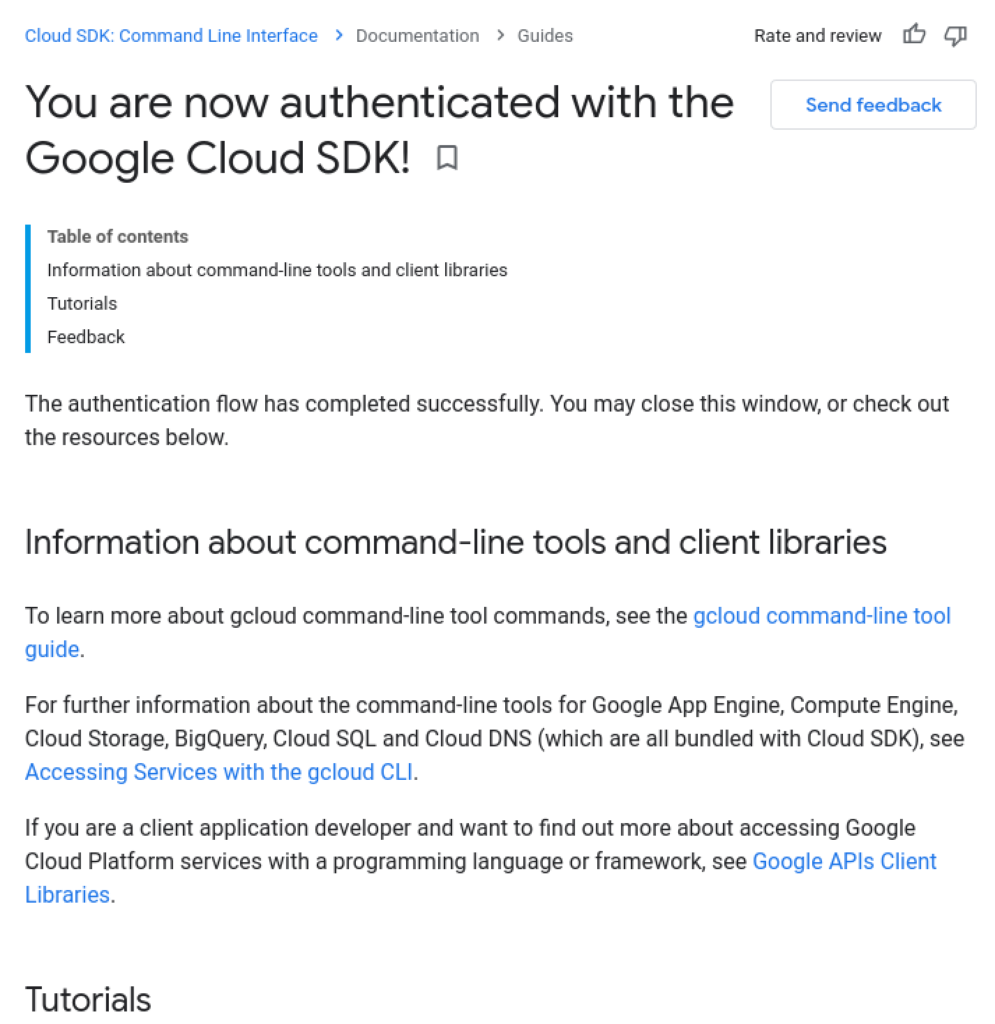

5. Confirmation message: In some cases, a successful authorization message is shown.

6. Application continues: The application has retrieved the user’s OAuth access token and can now access resources.

$ gcloud auth login [email protected] --force

Your browser has been opened to visit:

https://accounts.google.com/o/oauth2/auth?response_type=code&client_id=32555940559.apps.googleusercontent.com&redirect_uri=http%3A%2F%2Flocalhost%3A8085%2F&scope=openid+https%3A%2F%2Fwww.googleapis.com%2Fauth%2Fuserinfo.email+ht...

You are now logged in as [[email protected]].

$ gcloud projects list

Here is what’s happening under the hood of the above flow:

Device Authorization Grant

A new authorization flow, called device authorization grant, described in RFC 8628, was added in August 2019. Its purpose was to allow easier OAuth authorization on limited-input devices, such as smart TVs, where inputting credentials is tedious using TV remote controls, for enabling services such as video streaming subscriptions:

With device code authorization implemented, instead of the above, the user might see an authentication/authorization process that looks more like this:

Now, the user can use a richer-input device such as a smartphone or computer to enter a short code in a login screen with a short URL in order to authenticate and authorize the smart TV to access content such as the user’s streaming video subscription.

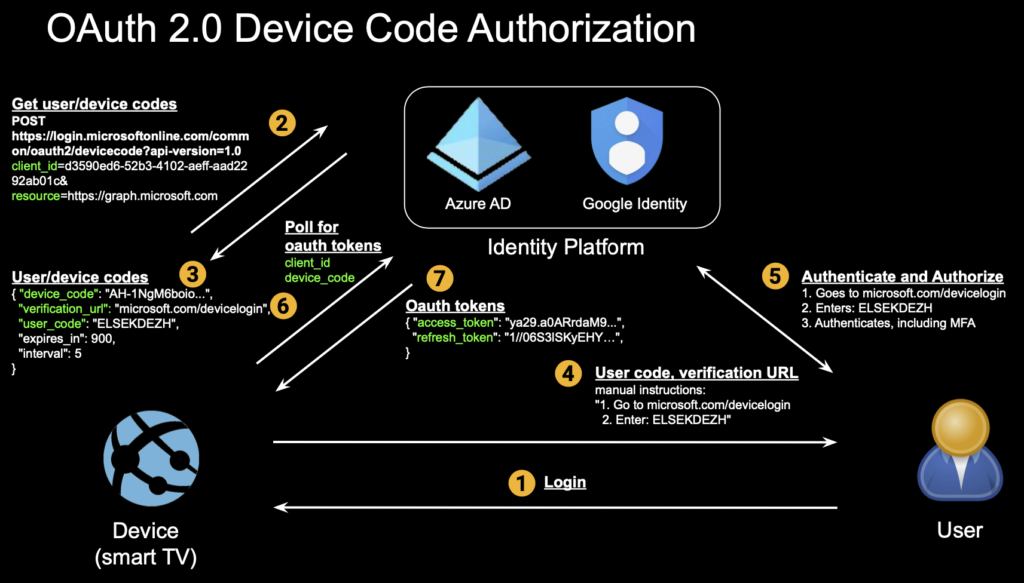

Underneath the above user experience is the device code flow:

Conclusion

There are at least three more flows in OAuth 2.0, and it’s fair to say that OAuth is complicated.

- It’s trying to bring secure authorization to complex interactions among three parties (identity/authorization provider, user, application/client/device), making it a challenge to secure against attackers who are looking to insert themselves into this process

- It’s difficult to understand, by users and security professionals alike, making it difficult to secure (e.g. “What’s this long code I’m looking at?”)

- It has to cover a variety of use cases including web server apps, native/mobile/desktop apps, devices, and javascript apps, with different flows for each, and with each flow having its own peculiarities and opportunities for abuse

At the same time, the OAuth protocol was not designed to address other important issues like the identity of each of the three parties. A user does authenticate with the identity system, but the application’s identity and, more importantly, the trustworthiness of the application is not addressed by OAuth. This, along with the complexity, leads to several areas that can be abused by attackers.

In Part 2, we will dig further into how a phishing attack is carried out using the device authorization grant flow.

Back

Back

Read the blog

Read the blog